You are probably familiar with Welch’s Grape Juice, but you may not know it has ties to the history of The United Methodist Church.

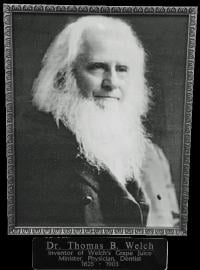

Thomas B. Welch developed a process for pasteurizing grape juice to keep it from fermenting. Photo by Roger Scull, of display at First United Methodist Church of Vineland, NJ.

In the 1800s, churches faced a dilemma. To combat the epidemic of alcoholism, the temperance movement advocated total abstinence from all alcohol. In celebration of the Lord’s Supper though, the church filled the communion chalice with wine.

Substituting grape juice seems an obvious solution. “For us today it is such common practice. We don’t know any different,” explains Adrienne Possenti, church historian at First United Methodist Church of Vineland, New Jersey.

In the 1800s, however, that was no easy task. Raw grape juice stored at room temperature—home refrigerators were not available until 1913—naturally ferments into wine. This caused a problem for congregations not wanting to use anything containing alcohol.

No suitable alternative

One solution was to squeeze grapes during the week and serve the juice before it fermented, but grapes were not readily available to every church.

“Lots of churches just didn’t have communion when grapes were out of season,” reports Roger Scull, also a church historian at First United Methodist Church of Vineland.

Some creative communion stewards chose to make their own unfermented sacramental wine. One recipe called for adding a pound of hand-squashed raisin pulp—dried grapes—to a quart of boiling water. Later in the process, the “winemaker” was to add an egg white. Doesn’t that sound delicious?

Some churches substituted water for wine. Many in the temperance movement declared water the only proper drink. Jesus’ miracle of turning water into wine at the wedding in Cana (John 2:1-12) seemed to give the practice a biblical justification.

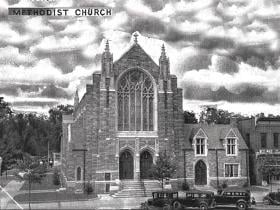

First United Methodist Church of Vineland, NJ, formerly Vineland Methodist Episcopal Church, is the birthplace of Welch's Grape Juice. Photo courtesy of Adrienne Possenti.

Most churches, however, simply continued to use wine. Not only did it solve the storage problem, it resolved another issue. Many believed the biblical mandate called for the use of wine, and viewed the sacrament as an exception to temperance.

Others claimed the wine used at the Last Supper must have been unfermented—not a widely held understanding today—and insisted on receiving the same.

The sometimes heated debate continued for decades.

In 1864, the General Conference of The Methodist Episcopal Church entered the conversation when they approved a report from the Temperance Committee that recommended “the pure juice of the grape be used in the celebration of the Lord's Supper.”

Thomas B. Welch, dentist

Four years later, Dr. Thomas B. Welch became a communion steward at Vineland (New Jersey) Methodist Episcopal Church—now First United Methodist Church of Vineland—and vowed to provide his congregation with an unfermented sacramental wine.

“He was so staunch in advocating not having anything to do with alcohol,” Possenti states, “it was reported that he didn’t want to even place his hands on it.” Possenti sometimes portrays Lucy Welch, Thomas’ wife, for schoolchildren and others in Vineland.

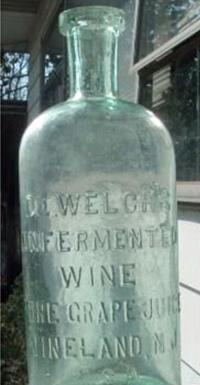

Welch's Grape Juice was originally labeled, “Dr. Welch’s Unfermented Wine, Pure Grape Juice, Vineland, NJ.” Photo courtesy of Adrienne Possenti.

Before moving to Vineland, Welch had served as a Wesleyan Methodist preacher. Throat problems that sometimes made it difficult for him to speak curtailed that ministry. In this newly established community, advertised as having a “healthful climate,” he opened a dental practice.

Always interested in science, Welch wondered if Louis Pasteur’s breakthrough techniques could be applied grape juice. He experimented to find a way to keep juice from fermenting.

In 1869, he perfected a juice pasteurization process in his kitchen and began selling “Dr. Welch’s Unfermented Wine” to churches preferring an alcohol-free substitute for Communion.

Unfortunately, the idea didn’t take off. After four years, Welch gave up this side business.

Two years later, his son Charles convinced him to produce unfermented wine again. Charles offered free samples of the sacramental wine substitute to churches. He later published temperance magazines that advocated alcohol-free Communion. He also advertised the product with lines like, “If your druggist hasn’t the kind that was used in Galilee containing not one particle of alcohol, write us for prices” (Pinney 389).

Temperance movement grows

At about the same time, the temperance movement and their concern over using fermented wine for communion, was gaining momentum.

By 1876, members of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) were refusing to receive the sacrament in churches using wine. The WCTU, organized in 1873, consisted largely of women from the Methodist Episcopal Church. Well-known Methodist Frances Willard served as their first secretary and second president.

Then, the 1880 General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church approved two changes to the Book of Discipline that may have been influenced by the work of the WCTU and the growing popularity of Welch’s Grape Juice.

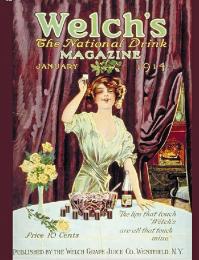

Charles Welch advertised by publishing magazines, and using slogans like, “The lips that touch Welch’s are all that touch mine.” Photo courtesy of Adrienne Possenti.

The first change provided an option. Churches were “to see that the Stewards provide unfermented wine for use in the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper.” Alcohol-free Communion was to be available in every church.

The second change, however, made it effectively mandatory, “Let none but the pure, unfermented juice of the grape be used in administering the Lord’s Supper, whenever practicable.”

“By the 1890s,” one author reports, “annual conferences of the Methodist Episcopal Church began including ads for Welch’s grape juice in their published journals” (O’Brien 219).

Welch’s expands

Charles Welch soon grew his new company beyond the church. He marketed grape juice as a health tonic, touting its medicinal uses. One advertisement recommended Welch’s for typhoid fever, pneumonia, and “all forms of chronic diseases except Diabetes Melitus” (Pinney 389).

When Charles offered samples at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, the popularity of Welch’s Grape Juice grew even more. Before long, it was advertised as “the national drink.”

Charles Welch summed up his dad and his life’s work in his will:

"Unfermented grape juice was born in 1869 out of a passion to serve God by helping His Church to give its communion 'the fruit of the vine,' instead of the “cup of devils.”

Today, Welch’s is a multinational corporation offering a number of grape and other fruit products. It all started, however, with a communion steward in a Methodist Episcopal church who wanted a suitable, unfermented wine for Communion.

*Joe Iovino works for UMC.org at United Methodist Communications. Contact him by email. This feature was originally published on June 28, 2016.

Resources:

O'Brien, Betty A. "The Lord's Supper: Fruit of the Vine or Cup of Devils?" Methodist History. 4th ed. Vol. XXXI. Madison, NJ: General Commission on Archives and History of The United Methodist Church, 1993. 203-23. July 1993. GCAH Virtual Reading Room. Web. June 8, 2016. http://archives.gcah.org/xmlui/handle/10516/5998.

Pinney, Thomas. A History of Wine in America: From the Beginnings to Prohibition. Berkeley: U of California, 1989. 383-90. Google Books. Web. June 8, 2016. https://books.google.com/books?id=fmcwfK5G_YkC&dq.