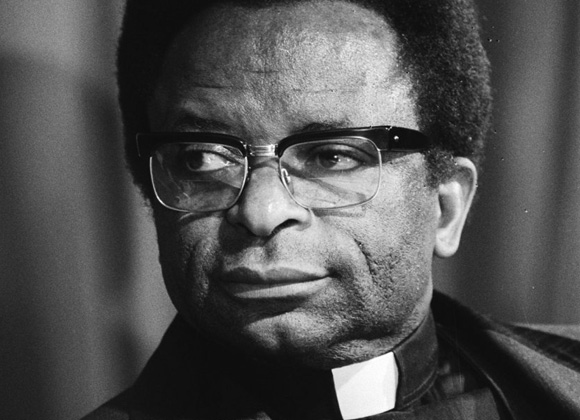

Bishop of Zimbabwe and National Leader

Bishop Abel Tendekayi Muzorewa, Methodist bishop and nationalist leader, was prime minister of the coalition government called Zimbabwe Rhodesia, which failed in its attempt to create a biracial government to end the civil war in formerly white-controlled Rhodesia.

In 1947, Muzorewa was appointed a lay preacher for five tiny congregations while he studied theology. He was ordained in 1953 and was appointed a circuit preacher for five years before spending 1958 to 1963 at Methodist colleges in the United States, where he completed a master’s degree.

By the 1950s he supported his people’s rising nationalist feelings and, after his return, he took up a conference post as youth director, where he could channel his ministry into political activity. He led protests against the deportation of Bishop Ralph Dodge, who opposed the increasing political repression of the Ian Smith government, which unilaterally proclaimed the independent white-ruled nation of Rhodesia in 1965.

In 1968, Muzorewa was elected bishop to succeed Dodge, becoming the first African head of a major church in Rhodesia. He came into conflict with the Smith regime, which banned him from tribal trust lands, where most of the black Methodists lived. He continued to criticize the racist policies of the government and became a national symbol of resistance.

In 1971, the British struck a deal with Smith that provided for a transition to majority rule over decades in exchange for an end to sanctions against the government. Muzorewa joined with an inexperienced cleric, Reverend Canaan Banana, to form the African National Congress (ANC) to oppose the settlement. It was so successful that the proposed referendum was withdrawn; Muzorewa found himself a national leader and an international personality. The liberation movements – the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) of Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole and the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) of Joshua Nkomo – both placed themselves under the ANC umbrella even though they had some doubts when Muzorewa founded a national party. The ANC was the only legal black party once ZANU and ZAPU undertook guerrilla warfare, which it rejected.

Muzorewa is a man without cunning or political guile, which was both his appeal during the 1970s and the reason for his failure. He was the acknowledged African leader, but he lacked ambition and avoided the factional politics that fueled the independence movements but which also led to ethnic violence and bloodshed in internecine battles. Muzorewa saw himself as a Moses leading his people out of bondage; ZAPU and ZANU saw him as a figure-head maintaining a legal front while they fought the real battle for liberation.

In 1975, Sithole and Nkomo were released from the restriction that had confined them to their home villages since 1964. They promptly moved to seize control of the ANC from Muzorewa. Talks with the government collapsed, Nkomo and Sithole abandoned the ANC to begin their own splinter movements, and Muzorewa temporarily left the country. After 14 months, he returned to a tumultuous welcome. Nkomo tried to outflank the bishop by joining with guerrilla leader Robert Mugabe to form the Patriotic Front (PF).

After the collapse of U.S.-brokered conciliation talks in 1977, Muzorewa found himself increasingly isolated politically. The neighboring African states endorsed the PF’s civil war, and Muzorewa turned to direct negotiations. In 1978, Muzorewa and Sithole (who had lost control of ZANU to Mugabe) signed an agreement with Smith for installing a majority government within a year. All citizens over 18 had the vote, but the seats were reserved for whites and they were allocated a quarter of the cabinet positions.

From the start the transitional government was doomed to failure. Muzorewa became prime minister when his ANC carried the elections and the country’s name was changed to Zimbabwe Rhodesia. But the PF denounced the arrangement, the war continued, and no international recognition was forthcoming. When Muzorewa attempted to address the United Nations Security Council the day after Nkomo and Mugabe, he was not permitted to do so. The security situation deteriorated until government supporters were unsafe beyond the region around the capital. Large numbers of whites emigrated, leaving the economy in shambles. Finally, an international all-party arrangement led to the arrival of a British administrator along with Commonwealth troops to oversee a cease-fire. In 1980 independence was achieved, and Mugabe’s ZANU swept to power. Muzorewa was elected to parliament, but the ANC won only two other seats. Banana became president of Zimbabwe, with Mugabe as prime minister. Muzorewa remained in parliament but was detained from 1983 to 1984. In 1985, he returned to Scarritt Theological Seminary in Memphis.

By Norbert C. Brockman

This article is reproduced from An African Biographical Dictionary, copyright © 1994, edited by Norbert C. Brockman, Santa Barbara, California. All rights reserved. It is taken, with permission, from the Dictionary of African Christian Biography.

Bibliography

Current Biography. New York: H. W. Wilson, 1940-.

Lipschutz, Mark R., and R. Kent Rasmussen. Dictionary of African Historical Biography. 2nd edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

Dickie, John and Alan Rake. Who’s Who in Africa. London: African Development, 1973.

Wiseman, John A. Political Leaders in Black Africa. Brookfield, VT: Edward Elgar Publishing, 1991.

Rake, Alan. Who’s Who in Africa: Leaders for the 1990s. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1992.

Additional reading: Muzorewa, Abel. Rise Up and Walk (1978).