Roy C. Nichols was the first African American elected to be a bishop in The United Methodist Church. He is remembered as a pioneering leader and advocate for social justice and racial equality who was at the forefront in the struggle for integration.

Born in 1918 in Hurlock, Maryland, the youngest of three children, Nichols heard his grandfather preach in neighborhood churches and felt his own call to ministry at the age of 8.

After graduating from Lincoln University in Philadelphia, he moved to Berkeley, California, in 1941 to attend seminary at Pacific School of Religion. As a young seminarian in 1943, he was called to serve as one of the two founding pastors of South Berkeley Community Church (Congregational), one of the area’s first intentionally integrated congregations.

“A Long Stride Forward,” a brief history of this pioneering church, helps set the scene. The country was in the midst of World War II with no end to the conflict in sight. During the war, large numbers of African Americans had migrated westward, with a growing population moving into the Berkeley area. This was what made this congregation, and Rev. Nichols’ involvement in it, possible.

“A Long Stride Forward” describes the launch of this congregation as “a daring new venture in human relations and interracial understanding. … [A few men and women decided] to light a candle rather than curse the darkness. That candle was the idea that men, regardless of race or nationality, could ‘walk together as Christian brethren.’ That candle, ignited in the oppressive gloom of World War II, was South Berkeley Community.”

Under the leadership of Nichols and his white co-pastor and fellow seminarian, Robert Winters, the church quickly grew and became known as “The Church Without Walls.” In the second year of his pastorate, Nichols married Dr. Ruth Richardson at the church.

More about Bishop Roy C. Nichols

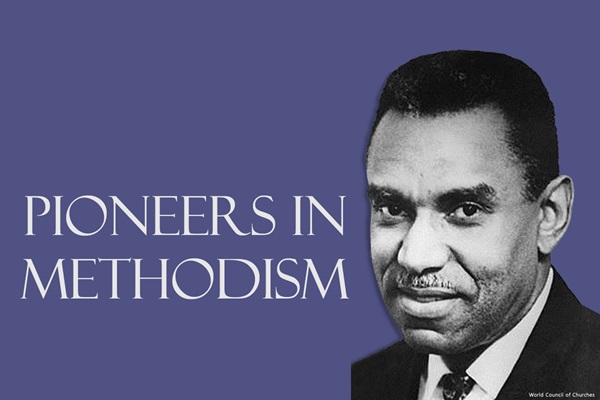

Photo of Bishop Roy C. Nichols courtesy of The General Board of Archives and History via The New York Annual Conference.

His Life and Legacy

Bishop Roy C. Nichols Senior Housing, Downs Memorial UMC

Berkeley Landmarks

Pastor Nichols with Martin Luther King, Jr.

Ordination Sermon, New York Conference, 1984

250 Year of Methodism in the New York Area

Bishop Roy C. Nichols Senior Housing, Downs Memorial UMC

Selected Sermons

Sermon at Black Methodists for Church Renewal, 1988

In 1949, Nichols became the founding pastor of another racially integrated congregation, Downs Memorial Methodist Church in Oakland. He also began hosting a popular radio show in the Bay Area called "The Christian Answer," which enabled his preaching to extend well beyond the church.

As Nichols continued his pastorate in Oakland, a growing number of members of the Bay Area community began pushing for a Black resident to serve on the local Board of Education. A Black board member could not be elected without support from the white community. In 1961, as a well-respected pastor of an integrated congregation, Nichols became the first African American to serve on the school board. During his last year at Downs Memorial (1963-1964), he served as president of the Berkeley Board of Education. During his tenure on the board, he worked for integrating schools, providing services for Black students and hiring more Black teachers.

In 1964, Nichols moved to New York City to become pastor of the 4,600-member Salem Methodist Church. Under his leadership, the congregation became deeply involved in serving its Harlem community, including constructing a million-dollar, four-story community center.

While there, Nichols extended the scope of his fight against segregation within the Methodist Church. The Methodist Church was formed in 1939 by the union of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, the Methodist Protestant Church and the Methodist Episcopal Church. As a condition of joining the union, the Methodist Episcopal Church, South required that the new Methodist Church create racially segregated structures for its Black members. These structures included a racially segregated jurisdiction (the Central Jurisdiction) and racially segregated annual conferences within it.

These racially segregated structures remained fully in force from 1939 until 1956, when the General Conference of the Methodist Church permitted the voluntary uniting of Black and white annual conferences sharing similar geography. But voluntary desegregation was not ending institutional segregation. As The Methodist Church and the Evangelical United Brethren were working toward a union of the two denominations, both Black members of the Methodist Church and the leadership of the Evangelical United Brethren insisted that racially segregated structures be abolished entirely as a condition for them to support the union. As a result, the 1968 Uniting Conference approved a motion to abolish the Central Jurisdiction and all racially segregated annual conferences, with a completion date no later than 1972.

Abolishing these racially segregated structures would not be enough to address the racism that had created those structures in the first place. Delegates to the 1968 conference were to decide on a proposal to form an agency focused on racial equality in the church. Rev. Nichols was asked to present to the delegates a substitute motion to that proposal that would provide specific direction and funding for the work of this agency, as opposed what he described as the “housekeeping measure” it would replace.

The substitute motion named the body being created “The Commission on Religion and Race,” included detailed guidance for its membership, including its Black membership, and gave the commission a mandate to be in cooperative relationship with “various prophetic movements for racial and social justices.” Nichols went on to state “[W]e want this General Conference to understand that this … is an effort on the part of black and white members of this General Conference to press The United Methodist Church into the position of leadership nationally and internationally on the subject of race and its concern.” After considerable debate, the substitute motion Nichols proposed was approved, and the General Commission on Religion and Race was established to hold the newly formed United Methodist Church accountable in its commitment to reject and eradicate the sin of racism in every aspect of the life of the church. (See pages 405 and following of Journal of The Uniting Conference of The United Methodist Church, 1968, Volume 1).

A few months later, in July 1968, the Northeastern Jurisdiction elected Nichols to the episcopate, the first Black bishop in the new denomination. He was assigned to serve as bishop of the Pittsburgh Area for 12 years, until 1980. In 1980, he was assigned to New York Area, where he retired in 1984.

In retirement, Rev. and Dr. Nichols returned to Oakland, where he served as bishop in residence at Downs Memorial United Methodist Church, and member and chairperson of the city's Human Relations Commission. Widely sought after as a speaker and church leader, he continued to address United Methodists around the world, to encourage the ongoing work of integration with justice and advocate access to education for people everywhere. In the latter role he became actively involved in the work of the development committee of Africa University.

In his sermon at the ordination service of the New York Annual Conference in 1984, Bishop Nichols shared his vision to encourage the newly ordained: “Take the truth, whatever amount you have learned, as God clarifies it, and invest it in the world, in the issues that affect the lives of people, their pain and their joy. The linkage of a life like that fulfills the expectation of Jesus when he said, ‘Ye are the salt of the earth and the light of the world.’”

After suffering a stroke in 1999, Bishop Nichols died in 2002 at the age of 84. He was more than just a pioneer. He created a continuing legacy as a servant of Christ committed to undoing the harmful effects of racism by building connections across racial lines and helping the disenfranchised claim their place as full members of the community.

This content was produced by Ask The UMC, the information service of United Methodist Communications.