Protestantism in Russia has a long, up-and-down history. Until the early 20th century, being a Protestant was a crime. Methodism came to Russia more than 120 years ago. Depending on the political environment, however, it has had periods of growth interrupted by times of struggle. Post-Soviet Russia has been more open. As The United Methodist Church has grown there, so has the need for more trained clergy.

Since the fall of communism in the early 1990s, United Methodists have placed a priority on strengthening and developing congregations and church leaders in the former Soviet Bloc countries of Eastern and Central Europe.

After the 2000 General Conference approved a resolution from the General Board of Higher Education and Ministry (GBHEM) to reinforce theological schools and expand ministerial programs in the region, the assembly approved a $3 million program to support theological education in the region's annual conferences.

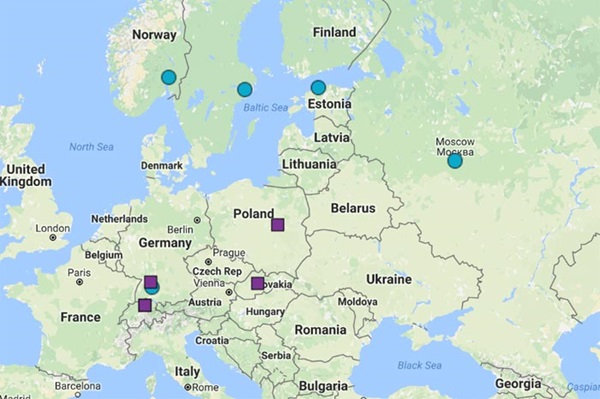

Seven United Methodist theological schools now serve Eastern Europe and Russia.

The Rev. Myron Wingfield, associate general secretary of GBHEM's Division of Ordained Ministry, cites these schools as an example of "the connection at its best."

The 1992 General Conference approved the Russia United Methodist Mission Conference; today, Eurasia is the largest geographical episcopal area in the denomination, covering 11 time zones.

In 1995, the Russia United Methodist Theological Seminary opened in Moscow. Today, the school has 50 students on its campus and another 40 attend three regional centers in central Asia, the Far East of Russia and Ukraine.

A challenge to the faculty charged with training pastors in United Methodist theology is that they must first make sure students know what it means to be United Methodist.

"As first-generation Christians, most United Methodists in Russia and Eurasia cannot learn what it means to be United Methodist from parents and grandparents. The seminary is the central place for leaders and pastors to learn Wesleyan teachings," says the Rev. Sergei V. Nikolaev, seminary president.

Wingfield sees similar issues in other Eastern European countries.

The current Russian government "is not interfering with the work of Christian institutions," Nikolaev notes.

Despite the small number of United Methodists in Russia, Nikolaev says high-quality graduates have no problem finding appointments there. Their challenge is to lead churches to become self-supportive. In some cases, congregations cannot fully support a pastor with a family, and those pastors must pursue bi-vocational ministry.

Nikolaev's goals for the seminary include increasing faculty with Ph.Ds. Currently, only one staff member has a doctorate; he hopes to increase that number to at least four.

One thing he is most pleased about is a multiyear project in which the Moscow Seminary engages. The project involves translating key Wesleyana into Russian, such as standard Wesley sermons, making them available online along with a critical edition for Russian readers.

Joey Butler is multi-media editor at UMCom in Nashville, Tennessee.

One of seven apportioned giving opportunities of The United Methodist Church, the World Service Fund is the financial lifeline to a long list of Christian mission and ministry throughout the denomination. Please encourage your leaders and congregations to support the World Service Fund apportionment at 100 percent.